(Success without Steroids)

Albert Einstein’s name was in the News a lot in the year 2000. He was no longer living, but was voted “The Man of the Twentieth Century” by most prominent magazines in our Nation and in the World. The publication of his “Relativity Theories” at the beginning of the 1900s, as well as some of his other prominent works, turned the world upside down with their simple but masterful, yet controversial innovations. When his theories were finally proven valid, and applicable to many areas of human endeavor, he was recognized as a genius, and truly the father of twentieth century enlightenment.

Complexity gives way to Organized Simplicity

The “Home-Run Principle” is a formula that will explain the mechanics of hitting a home-run, not with complicated mathematical equations (nor chemically induced enhancements), but rather in terms of the simplicity that Einstein discovered in his “Relativity” theories as well as his Photo-Electric Effect that gave birth to the rationale for “Quantum Physics.”

Baseball teams and many players, both professional and amateur, have adopted, over the past years, various theories for what they hoped would be instrumental in effectively hitting a baseball. However, the “Scientific Community” would probably balk at the proposed hypotheses of those misguided seekers of masterful bats-man-ship. Unfortunately, these “pseudo-Einsteins” have managed to convince a large body of Baseball’s intelligentsia and “blue-collar” artisans of the practicality of some of the most preposterous ideas for properly hitting a baseball.

One common theory that seems to have captured the imagination of prominent baseball enthusiasts within the last decades, or so, is that one which prescribes the utilization of the force of gravity to facilitate the mechanics of swinging a baseball bat in a downward arc. The purpose would be to contact the speeding baseball in such a way as to precisely “slice” the front end of the ball to get the backward spin that would allow it to carry over a greater distance than would a ball that makes flat-solid contact with a bat. Also, it might be supposed that stronger muscles come into play to facilitate a more powerful swing.

This idea of back-spin was extrapolated no doubt by someone whose human perceptions alertly noticed that a tight backspin cut through the resistance of the air better than did squarely-hit balls that “knuckled” and dropped rapidly. The premise that “back-spin” for the “home-run” ball is more desirable than “top-spin” is sound; but the conclusion that such spin can be artificially produced by an exaggerated, downward swing is too absurd for rational thinkers to accept.

With all the variables presented to a batter as he is attempting to strike a baseball in a most productive manner, the last thing he wants to do is to have his entire hitting mechanism suddenly governed by the extent to which he correctly applies the Pythagorean Theorem (“…the sum of the squares of the sides of a right triangle is equal to the square of the length of the hypotenuse”). The batter, in the batter’s box, is standing 60+ feet from the pitcher, on a plane almost 1 foot below the level of the “pitching-rubber.” An astute “bats-person” must realize that any ball thrown from a height range of 5 to 7 feet would have to follow a descending line or arc, in order to enter the batter’s strike zone.  Therefore, any batter whose notion of proper hitting technique includes the proposition that a downward swinging bat can effectively strike a downward moving ball with the least margin of error does not understand the statistical improbability of such folly. Such is the trademark of the “under-.270 hitter.”

Therefore, any batter whose notion of proper hitting technique includes the proposition that a downward swinging bat can effectively strike a downward moving ball with the least margin of error does not understand the statistical improbability of such folly. Such is the trademark of the “under-.270 hitter.”

Those confused individuals, who have experienced some success with the “Downward” technique, usually evaluate that success based on the amount of “seeing-eye” base-hits they produce rather than on the true quality of the “bat-to-ball” contact. Of those hits, the highest percentage is on ground balls that find a way through the infield. The “line-drives” that are deflected somewhat parallel to the ground are the few examples of the bat meeting the ball perfectly, at the right time, at the perfect angle, to effect a preferred result. The probability of this desirable effect happening in a high percentage of “at bats” is unlikely.

Higher Probability for Success?

Most professional baseball players have good hand-eye coordination. When they swing down on a ball they will very often make solid contact. Therefore, in most hitting situations, the best that an effective batsman can do is hit a ground ball. Or if he really hits it squarely, he can hit a high bouncing ball. And the only way for something productive to happen is for the ball to get between two infielders, for a base hit.

By knowing that a pitched ball is always traveling downward into the strike-zone, the intelligent batter will devise a technique that will ensure that the bat will strike the ball on a line as close to 180 degrees as is possible.  To be 100% accurate with his guidance of the bat-to-ball is most improbable. But if the swinging bat is on the same parallel line as the in-coming ball, then the probability of solid contact will be strong, and the result most often will be a desirable ascending “line-drive.” If the ball is miss-hit because the bat strikes it slightly above or below the center of its diameter, the effect will also be positive. “Slightly under” (forcing tight back-spin) will facilitate a long, high, “carrying” drive (home-run type); while “slightly above” (forcing tight topspin) will facilitate a hard looping line drive.

To be 100% accurate with his guidance of the bat-to-ball is most improbable. But if the swinging bat is on the same parallel line as the in-coming ball, then the probability of solid contact will be strong, and the result most often will be a desirable ascending “line-drive.” If the ball is miss-hit because the bat strikes it slightly above or below the center of its diameter, the effect will also be positive. “Slightly under” (forcing tight back-spin) will facilitate a long, high, “carrying” drive (home-run type); while “slightly above” (forcing tight topspin) will facilitate a hard looping line drive.

The “Home-Run Principle,” is a fundamental basis upon which the application of the proper mechanics of hitting a baseball can influence the quality and productivity of the stroke. This process includes so vast an array of variables that it is no wonder it would take an Einstein and his use of Quantum Physics to ordinarily deploy the probable determinants for consistent home-run hitting.

Is Strength the Key?

Most baseball analysts subscribe to the notion that a batter has to be extremely strong to be a consistent home-run hitter. (This is why every extreme aspirant to contemporary “Baseball-Glory” unwittingly ascribes to steroid enhancement!) While strength is an asset, mechanics play a more important role! If a person is capable of hitting one Home-run, he is capable of hitting seventy or more, if all the required conditions are present every time.

A “weak” player, who has hit a home-run, did so because he was able to apply the proper mechanics to his stroke, at the appropriate pitch, at the correct time. Theoretically, he should be able to repeat this action, at least every time the same conditions are present.

A “weak” player, who has hit a home-run, did so because he was able to apply the proper mechanics to his stroke, at the appropriate pitch, at the correct time. Theoretically, he should be able to repeat this action, at least every time the same conditions are present.

Every mature adult (male), who is not hampered by some physical encumbrance, has the strength to hit a home-run! What he may not have is the specific coordination and mechanical understanding that facilitates the home-run stroke.

Most people think that Mark McGwire and Barry Bonds have hit a lot of Home-runs because they’re so big and strong. But it’s because of the intelligent and consistent manner in which they applied the “Home-Run Principle” to their hitting mechanics that they’re such prolific home-run hitters.

Their strength was a factor (steroid induced, or not) with regard to the distance they consistently hit their home-runs. The extent to which a normal person’s “warning-track” shot is caught and theirs’ make it over the fence is directly attributable to strength. But a normal person’s “warning track shot” is only due to the fact that something was missing in the vast dynamics of the swing, which precluded the ultimate function. If all preliminary conditions were met at the “contact point,” the launch would have carried over the fence.

Key Components

The “Home-Run Principle” is based on the perfect application and integration of following components:

- Balance and stability of the stance.

- Security for undisturbed visual acuity.

- Self-contained power source.

- Balance and stability from start to finish of swing.

- A low center of gravity can be established by spreading the feet to the width of one’s normal stride, and bending the knees as low as can accommodate comfort and quickness. This strong base affords the batter the fastest possible reaction time for a twisting body to respond to any variation of pitched balls. One of the most prominent features of a low stance is the obvious advantage the batter has with the establishment of a smaller strike-zone.

- With the low-wide stance, the batter is in an “ultra-stationary” position, from which to view the pitched ball with a minimum of distortion. As a tennis, or “table-tennis” player, receiving serve, is bent over and down as low as he can, to see the speeding ball on as close to a parallel level to the eyes as possible, so the batter, in a low stance, views the pitched ball with most clarity.

- With the body already in a stable and powerful position, from which to initiate the action of the swing, the only preliminary movement needed by the batter, as the pitcher is delivering the ball, is to brace himself (or “gather”). From there he awaits the arrival of the ball into the striking “zone.” The gathering simply implies that the front part of the body is twisting or coiling slightly in the direction toward the catcher, bringing the hands to a position just beyond the back shoulder, making ready for the body to “recoil” as the ball comes to the plate. The “coiling” is initiated by the front knee turning inwardly off a pivoting big toe. While the back foot is anchored flat, the weight of the body is centered from the upper abdomen to the ground directly between both knees. The hips and shoulders follow the backward rotation of the twisting torso (the body never leaning backward with any concentration of weight on the back leg—the “buttocks” looks to be sitting on a high stool). The entire action of the backward twisting and subsequent forward explosion in the opposite direction, as the swing takes place, occurs while the head remains stationary and the eyes still, focusing on the ball. The fulcrum for the hip-action in the perfect baseball swing is neither the front nor the back, but rather the center, as both the front and back (hips) work synergistically to maximize the speed of the turn along a constant vertical axis and horizontal plane. The front foot secures the ground with such force from the straightening front leg that the front hip is being forced open as the back hip is driven forward with equipollence by the aid of a forward driving back bent-knee. If performed properly, the vertical axis of spine and upper body remains constant while the hips are rotating along a consistent horizontal plane.

- After the swing has been completed, every part of the body will have rotated around and under the “fixed” head. The height level of the batter at the end of the swing should be approximately the same as it was at the beginning. Stability and balance at the end is as important as at the beginning. This order procures maximum efficiency for the sensitive guidance system which the forces of the body provide to the eyes and head.

What Constitutes Maximum Visual Acuity?

Everyone realizes how important it is to see properly in order to perform well. And all athletes are required to perform well, even while their entire bodies are in motion. Outfielders and infielders have to run or move abruptly to catch balls, and most do so very proficiently. No professional baseball player has trouble catching a ball while he is standing still and keeping the ball at eye-level.

There are some prominent “Hitters” in baseball whose abilities seem little diminished by the subtle head-movement in their batting styles. But, “congratulations” to those .300 hitters who intuitively realize that the least amount of head-movement has a direct relationship to successful “bats-man-ship.” Conversely, the more pronounced the head movement, the lower the batting effectiveness. Great athletes seem to have the ability to make certain physical adaptations that allow them to counteract visual distortions, some of the time (especially in their younger years), to maintain a respectable productivity. But, if all hitters would recognize that they are not sacrificing power by eliminating the “stride” and keeping the head still, their current batting performances would improve.

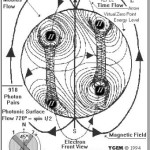

Einstein’s Special Relativity Theory states that “…the laws of physics are exactly the same for all observers in uniform motion.” Along with his contribution to the establishment of Quantum Physics that informally states, that “at the fundamental levels of matter, causation is a matter of statistical probabilities, not certainties,” Einstein’s revelations impart practical appliance to the “art of hitting a home run.” Since Einstein’s theories center around his study and application of the characteristics and qualities of light, all of humanity can capitalize on their utilization in the most practical of ways.

When a baseball enthusiast is watching a game at home or at the ballpark, he will periodically tell himself that he definitely could have hit the ball that the batter just missed. He saw it perfectly! The catcher behind the plate often wonders why he’s not a better hitter than he is. After all, “when I’m catching, I have no trouble seeing the ball all the way! Even curves, screwballs, splitters, knuckle-balls, etc.” Since the laws of physics are exactly the same for all observers in uniform motion, why is the batter’s perception of the moving ball different from that of the spectator or the motionless catcher (or even the “faculty-diminished” umpire)? The most probable answer is that the batter’s eyes are not seeing as the eyes of these “spectators” are seeing, as Einstein’s revelation of “time-dilation” would indicate—the phenomenon of different times for different observers. A similarly remarkable observation was made by another highly esteemed authority from an earlier era when he said, “…the light of the body is eye; if thine eye be single, thy whole body shall be full of light.” Be still and focus!

Most Difficult Task

If Einstein were a sports enthusiast, he’d probably not agree specifically with the Ted Williams statement that “hitting a baseball is the single-most difficult thing to do in all of sports.” He’d probably say that, “hitting a home-run is the single-most difficult thing to do in all of sports.” To hit a home run, a batter has to be almost perfect in his application of the “the laws of physics” with regard to the mechanics of swinging a baseball bat with precision and power. To be a consistent home-run hitter the batter must also have an understanding of all the elements that are included in the dynamics of hitting a home run. Theoretically, it is possible to hit a home run every time a batter swings at a baseball. However, as Einstein and others have found, through Quantum Mechanics, when trying to establish the essence of matter, that “at the fundamental levels, causation is a matter of statistical probabilities, not certainties.”

Therefore, with all the elements and combinations of variables with which a batter has to deal, from within and from without himself, the “uncertainty principle” gives compelling testimony that mastering the “rubik’s cube” of hitting a home-run every time is highly improbable. However, the knowledge itself, of such feasibility, enhances the statistical probability of success.

Statistically Consistent Home Run Hitter

Statistics are formulated from the accumulation, analysis, interpretation, and presentation of specific data, hopefully to be applied to a practical use. Home run hitting could very easily fit into the category of such practical use to some aspiring Major-Leaguer. (Application of Home Run Principle will preclude the need for “steroids”)

If one is familiar with all the “specific data,” and his analysis and interpretation are correct, he can reasonably assume that his chance of improving on his current output is at least statistically promising. But, even if one has all the knowledge and understanding from the processed “data,” by what means does he put a practical plan into action to complete his quest for being a Home-run hitter?

With complete assurance that the Principle is sound and applicable, the “disciple” must then practice. But only “perfect practice” will suffice until the perfect swing is established. There are gradations of practice sessions to be accommodated before the final testing period against legitimate pitching, in game situations, can be warranted. These gradations begin at the lowest possible level and evolve as perfection in each step has been mastered.

Gradation of “Perfect Practice”

The physical dimension of this practice of Principle (from within) can be enhanced with the application of the following multi-step hitting drill:

FOR HITTING: Four things happen at the same time, with the upper and lower portions of the body, at the critical point where the transfer of weight comes into play. The front foot plants and knee begins straightening (forcing “front hip” backwards). The back bent-knee rotates forward with thrust from the inner thigh and groin (helping to pull the “back hip” forward. The front shoulder shrugs upward (at first impulse), and pulls backwards (at second impulse). The back elbow (with shoulder) drives down and forward (by means of “Pecs. and Lats.”). All this happens at the same time before the arms and hands bring the bat to the striking position. To be done perfectly, the head has to remain perfectly still as the entire body rotates under it. As the bent back knee reaches its forward-most point, the head is directly above it through the swing.

Always remember that the speed and power of the swing is determined by the speed of the hips and shoulders. The effectiveness of the hip-action is determined by the bent back knee, which helps keep the bat on a “level” plane when the swing begins. If the back leg begins to straighten during the swing, the head and body lunge forward and upward, and the bat inadvertently goes over the ball, not to mention compromising the integrity of vertical and horizontal axes. Also, moving forward to hit the speeding ball has a set of potential problems of its own.

4-STEP HITTING DRILL: This should be done without a bat first, then with a bat after total coordination has been mastered.

Step 1 – Assume a position of maximum strength and balance. Get as low a stance as to not feel too uncomfortable, with feet spread at the distance of your normal stride. (Remember, a low stance gives you a natural advantage of a smaller strike zone, as well as a fundamental posture for stronger and quicker movement. If you understand the value of this “principle,” any physical discomfort you seem to have with a low stance will diminish as your body becomes acclimated, through repetition and positive results.) Then begin the repetition of the entire hip-shoulder “weight-transfer,” step by step. Repeat five attempts, focusing on the straightening of the front leg. Push down hard on the front foot, with the feeling of pushing your body backward. If the body actually does fall backwards, off balance, your back foot and bent knee did not do what was required of them.

Step 2– Focus on the action of the back leg. With a low stance, as you assume that the transfer of weight is imminent, drive the back bent-knee forward with force, rotating from the outside of the big toe of the back foot. Focus on the back leg during the simulation, but be conscious of the other three stages (especially the front leg). The vertical axis should remain intact, the head, spine, and hips on the same vertical plane, while the hips are rotating horizontally around that same vertical plane.

Step 3—Focus on front shoulder action. As front foot is planting, be focused on how forcefully you can shrug and pull the front shoulder up and backward. If the movement feels weak, it’s probably because the hips did not initiate the action.

Step 4—Focus on back shoulder and elbow. When the front shoulder shrugs, the back shoulder (with elbow) automatically lowers. The muscles of the Pectoral (in chest) and Latissimus (in back) areas drive the back elbow down and forward ahead of the back hand. The hand is thus in a palm-up position to force a flat bat through the ball. So, focus on the backside of the upper body coming through. But be conscious that the front side seems to be initiating the action.

After these four steps have been mastered, use a bat and go through them again using a batting tee until mastery is attained. After that, go through the same procedure, this time combining step one with step two, and step three with step four, making it a two-step drill.

Remember, you are working to see how fast you can complete the entire action “perfectly.” Eventually you can move the tee to cover all the areas of the strike zone. If you notice that most of the balls are not being stroked in an ascending “line-drive,” then you may want to break the swing down again, with both “one-arm drills” (front first, then back). If you’re not familiar with the “one-arm” drills, they are merely simulations of the normal swing, using just the front or the back arm separately.

Remember, to assure that the head not move, refrain from taking a stride—you really don’t need it anyway, if you perfect the “four step” drill. When you feel that a mastery of these elements has occurred, you are ready to advance to a set of “soft-toss” drills. The mastery over these will qualify you for higher steps, until a state of extreme readiness is reached. Then your hitting mechanism will be finely tuned to near- flawless application for simulated game conditions. After this, your only challenges will come from the actual live pitchers you will face in actual game situations.

Physical and Mental Competency

So, will you be ready? Physically, you will be! Will that be enough? No! You must consult your “statistical data” for an understanding of the other facets that are involved in hitting—those that apply to the challenges that come from “without.”

The pitcher may want to assert his mastery over you and deny absolute validity to the application of your proven Principle. And that is the only recourse he has. Since your principle is sound, he must deny you the right to perfect application. He can do this only by abiding by the same mechanism of statistical probabilities as you. Remember Einstein’s “special relativity” correctly asserts that “the laws of physics are exactly the same for all observers in uniform motion.” And from what has been statistically certified over the history of pitcher-batter relationships, the disproportionate advantage to the pitcher is what now needs to be denied. The Home-run Principle can now assert a more pronounced effectiveness against the statistical dominance of the “Premier Pitcher Principle”– (which is merely an illusion).

The missing link in applying the hitting principle has always been the inconsistent visual acuity of the batter in accurately detecting the speed of the fast-ball, as well as the direction and varying speeds of “breaking” and other off-speed pitches. All this, of course, was due to excessive movement of the head, the primary culprits being the high stance and batter’s stride. Although the pitcher’s arsenal of distracting and illusory forces will always wreak their havoc on unsuspecting “head-gliders,” the Einsteins of a new era of batting prominence will set the standard for Home-run-hitting elegance.

Coming Next: Perfect Timing is what Focus is all about.