When classifying the “Greatest Home-Runs” in Baseball history, the closest that Kirk Gibson’s 1988 World Series “Bomb” ranks to the top of the analysts’ charts, even by MLB Productions, is 2nd or 3rd, behind Bill Mazeroski’s 1960 “Walk-off”, and/or Bobby Thompson’s 1951 “Shot Heard Round the World,” that gave the Giants the pennant.

Of course the main criteria for evaluating these enduring historical footnotes are still the reminiscence of “that” notorious City-Team rivalry and a purely “Under-Dog” sentimentality (Giants’ 15 games deficit before tying the Dodgers, then winning the pennant; and Pirates’ monstrous negative run differential with the overwhelmingly favorite Yankees).

Now, if that criterion cannot be upgraded eventually by Time and Logistics, then a new category must be conceived in order to pay proper respect for what Kirk Gibson did in 1988 when single-handedly, but surreptitiously, leading the Dodgers to the World Series Title. (Space in this category would also have to be reserved for NFL Football’s 1972 “Immaculate- Reception”, which would probably rank 2nd as the “penultimate” contributor to those “Amazing” performances.)

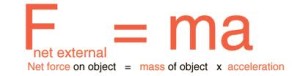

In order to hit a single home run, so many aspects of a batter’s swing must be aligned to satisfy the anatomical, physiological, and psychological constituencies composing each player, as afforded haphazardly by the “gods of Baseball”. Most athletes, professional and amateur alike, who have legitimately tasted both the “thrill and agony” of most majors sports activities will usually attest to the validity of Ted Williams’ famous yet arguable statement that, “hitting a baseball is the single-most difficult skill to master in all of Sports”.

In an essay I wrote entitled, “Einstein and the Home-Run Principle,” Einstein supersedes the Williams’ statement when he parenthetically observes, “Hitting a Home-run is the most difficult thing to do in all of Sports.” To hit a home run, a batter has to be almost perfect in his application of the “the laws of physics” with regard to the mechanics of swinging a baseball bat with precision and power. To be a consistent home-run hitter the batter must also have an understanding of all the elements that are included in the dynamics of hitting a baseball effectively. Theoretically, it is possible to hit a home run every time a batter swings at a baseball. However, Einstein and others have found through Quantum Mechanics, when trying to establish the essence of matter, that “at the fundamental levels, causation is a matter of statistical probabilities, not certainties.”Therefore, with all the elements and combinations of variables with which a batter has to deal, from within and from without himself, the “uncertainty principle” gives compelling testimony that mastering the “rubik’s cube” of hitting a home-run every time is highly improbable. However, the knowledge itself, of such feasibility, enhances the statistical probability of success.

Not even Albert Einstein and all the renowned physicists of his time, and “saber-metricians” of this modern-era, could have approximated the statistical improbability of what Gibson did on October 15, 1988. The resounding joy that New Yorkers experienced in 1951 and preserved for decades was not altogether incalculable, since Bobby Thompson had not more than 3 days earlier lit up Ralph Branca with a Home Run that presented as an ominous note a precursor of what was to come. And Bill Mazeroski’s feat that ended the 1960 World Series, although dramatic, cannot have been totally unexpected. Pinch hitter, Hal Smith, had earlier hit a 3-run homer to stake the Pirates to a 2-run lead until the Yankees tied the game in the top of the ninth, thus extending the heart-pounding “see-saw” battle. “Maz” was 1 for 3 as he led off the bottom of the ninth. Yankee pitcher, Ralph Terry, made the huge mistake of getting the pitch up to the short but powerfully built Pirate second base-man, who took advantage and slugged the ball over the brick wall 408 feet from Home Plate. It was truly a magnificent and endearing moment for the Pittsburgh community and all Baseball fans outside of the Bronx – worthy indeed of memorial status.

All that being said, encomiums to those two distinct episodes in Baseball lore should pale in comparison to the near “mythical” grandeur that highlighted the glorified instant of Gibson’s exalted “blast”, as well as propagated the ecstatic drama that preceded his culminating heroics. Kirk’s advent into professional baseball is as mysterious as that of the legendary “Roy Hobbs”, without the tragic prelude. Upon completing a successful College football career, it was suggested that he not waste his athletic talent in the “off-season” and play “a little” baseball for his Spartan baseball team at Michigan State University. In that first and only year of College baseball, he played so well (.390 B.A., 16 HRs. 52 RBIs. in 48 games) as to warrant being picked in the first round of the 1978 MLB Draft by the Detroit Tigers. He was with the Tigers for 9 years, and was a key figure in attaining a World Series title in 1984. After being determined as one of the ballplayers being “black-balled” by MLB Franchises in the notorious “Collusion Scandal” of 1987, he left the A.L. Tigers and in January joined the Hapless Dodgers of the National League, whose dismal ‘87 season needed something of a “Hobbsian” spark to generate new life into a ball-club in disarray.

At Spring Training a few opportunities presented themselves early in Camp to set the stage for an immediate change of direction in Team attitude and focus that would eventually lead the march to a much improved status and uncontested standing in the National League West to win the Division by 7 games. Frivolity and practical jokes took a back seat to Kirk’s ultra-professional and business-like mentality, and the team flourished from beginning ‘till the season ended. His season ending stats earned him National League MVP honors while helping the Dodgers win 21 more games than the season before. But it was his uncommon “personal-leadership” and otherwise intangible, undaunted presence that invoked the “mythical hero” image his teammates and adversaries had learned to admire and would attempt to emulate. In the NLCS, although injured, Kirk still performed heroically in clutch situations, and his timely home runs in the 4th and 5th games clinched the National League Pennant, and advanced the Dodgers into an improbable World Series entitlement.

Kirk purportedly had done all he could to get the Dodgers to that World Series, but “they” were presumably going to have to get to the “Promised Land” without him, for the injuries he incurred along the way were too severe for any “mortal” to overcome and give a last ditch effort. All the world would have accredited the Dodgers with a valiant effort for just making it to the “Final” Series because everyone knew that even with Gibson, there was slim if any chance for them to beat the powerful Oakland Athletics, whose superior arsenal of player personnel had amassed an incredible record of 104 wins to 58 losses. And even with Kirk’s Premier status with the “baseball gods,” the “Arrogant- As” knew that “one player does not a team make”.

With Gibson being an “absolute” scratch from the line-up (he wasn’t even at the pre-game introductions ceremony), the first game of the Series began unexpectedly with a first inning 2-run homer by Dodger, Mickey Hatcher. The “As” came back with 4 runs in the top of the 2nd, and held a 2 run lead until the Dodgers scored again in the 6th. The game remained at 4 to 3, Oakland leading in the bottom of the 9th.

Throughout the game, there were brief TV glimpses of Kirk Gibson hobbling around in the dug-out as he was traversing the distance from the training room and back, trying to massage and loosen his painful joints and hamstrings. Ever-optimistic, Tommy Lasorda seemed to be coaxing his beleaguered star, to see if any type of “miracle” was in the offing. Vince Scully repeatedly commented that there was “absolutely” no chance of Gibson making an official appearance. With T.V. and radio broadcasts coming into the locker room, Gibson heard one of Scully’s commentaries as if providence were beckoning for him to consider an alternative thought. In sudden contemplation of all that was transpiring before him, Kirk realized an inexplicable surge of unwarranted confidence streaming through his consciousness. As in a biblical reference to Jacob wrestling with the “man” inside, Kirk’s vision of Princely accommodation could not be suppressed. The decision was made; his mind was determined; “the die was cast”; but only the portentous action itself was forestalled. “Will I look like and be a fool? What in hell could I possibly do? I can’t even walk! What or Who do I think I am?” would have been the common queries instigated by mortal fear that must be wrested away from that mind intent on fulfilling a noble purpose.

After Dodger pitching blanked the Athletics in the top of the ninth, the otherwise stalwart performance of Oakland Pitcher, Dave Steward, ended when statistically prudent “As” manager, Tony LaRussa replaced his Starter with the League’s Premier “closer”, Dennis Eckersley. It looked like a sure win for Oakland, since “Eck” was destined to face the bottom of the Dodger line-up (though somewhat of an ominous sign, in hind-sight). Eckersley got the first two outs in rapid succession, and was about to face a formidable, former teammate who was set to pinch-hit for the 8th batter in the line-up.

Meanwhile, in the Dodger dug-out, Lasorda learned that Gibson had begun a personalized mental and physical rehabilitation process, which immediately spurred Tommy’s ever-percolating mind to envision a preemptive scenario of his own. After appointing Mike Davis to pinch hit for Alfredo Griffin, he surreptitiously placed Dave Anderson in the on-deck circle, to make Eckersley and LaRussa think that they could afford to be a little cautious with Davis (a potential threat) and contemplate the “end” by pitching to the very weak-hitting Anderson.

All potentially constructive Dodger strategy lay in the proposition that Gibson regain a semblance of his former self. Yet, even if he could overcome the acute pain and obvious debility, what could he hope to achieve in this debilitative condition? Bob Costas would later remark that while he was in the stairwell of the Dodger dug-out, he could hear the groaning, anguishing strokes of a batter desperately trying to ready himself for one last at-bat, even “one last-swing”, while teammate Orel Hershiser was feeding baseballs onto the tee for Gibson’s convenience. Although most of his teammates must have sensed the futility of Kirk’s somewhat contrived heroism, they probably also could not have expected anything less from “the man” who had proven himself so many times before. They all must have thought the “good-prospect” all but possible, however their past experience would at least warrant a “statistically” derived- at chance of success. “YOU’VE GOT TO BELIEVE” would have been the genuine inspirational sentiment pouring into the ears of the players from the mouth and heart of Tommy Lasorda and the Great Dodger in the Sky.

Kirk is now sitting at the end of the dugout bench, fully dressed, and armed with helmet and “hickory”, speculating the purview the situation has presented. “I have inspiration and commitment to do something, but what, and how far can my own determination carry me? Will Davis get on base to set up my ‘grand entrance’, and what emotion will the fans exude? And will it give me that final burst of adrenaline to be propelled to heights previously unknown?”

Gibson was afforded no additional time to mentally peruse the circumstances of the present situation, for Eckersley just walked Mike Davis. Taking a deep yet unstrained breath, Kirk’s electrifying and confident image popped onto the top step, then out of the dugout to the thunderous roar of the now ecstatic and frenzied crowd.

“That’s what I wanted to hear”, thought Gibson, as he must have restrained the urge to shed at least a tributary tear of ineffable joy he and his patrons could feel in this present moment of triumphal hope. Lasorda’s unending chants of “new promise” inspired his Team and the Dodger Faithful to loftier heights of exaltation, as Kirk finished his preliminary swings. His slow, deliberate, but majestic walk to the plate must have been a nerve-wrenching ordeal for the Oakland pitcher, even though he exuded a confidence rather than impatience to get the game over.

One could only speculate as to what order of thoughts must have been aligning themselves in Gibson’s mind as his footsteps proceeded into that rarefied cubicle of variable distinction. Before assuming his characteristically “Spartan” batting-stance, his back cleat scratched the hardened dirt for a foothold to secure a base from which his afflicted body might launch its purposeful attack. He was finally ready, and none too soon for the exasperated Eckersley, who let his arm commence with the business at hand, firing a blazing, side-arm, tailing fastball, for which Gibson must have felt a tad unprepared. All observers couldn’t help but notice the constrained, oblique wrenching, late response Gibson’s off-balanced body and bat conveyed as it almost completely missed the ball. The second pitch gave the same explicit message, and the fans as well as Eckersley himself must have sensed that “the Gibber” was no match for the “Eck”. Kirk was behind 0 and 2 in what seemed like a “heart-beat”, and Dennis was determined to finish him off on the next pitch.

Eckersley’s disdain for Gibson’s futile attempts was obvious as he was about to throw another fast ball, same speed, to the same spot (away). The fact that Kirk looked bad, but progressively better on each swing did not escape Eckersley discerning eye. Gibson knew that his body needed only a short quick turn, but even that was too slow to get his arms activated. On that third fast-ball, Kirk was prepared to shorten the turn and throw his arms and hands more quickly. The result was a swing with little power, as his arms and hands were too far out in front and his wrists rolled over way too soon. He was grateful that he even made contact for an otherwise worthless dribbler that forced him to run toward first before the ball fortuitously struck the edge of the infield grass and abruptly darted foul, thus extending his at-bat. (That had to hurt!)

After his first pitch to Gibson, it became obvious to Eckersley, as well as the “brain-trusts” in both dugouts, that Kirk was not the optimum threat for which everyone fancifully hoped or cautiously suspected. But he was quickly portending to be a formidable adversary, even in his seemingly “powerless” condition. “Eck” recognized that with all the pitches Gibson was subtly calculating, making superficial contact with every one, it might only be a matter of time before he can put one in play, perhaps to the detriment of Oakland. Therefore, he can’t let Davis steal second base. Before his second and third pitches he made 3 throws to keep Davis close. With 2 strikes on Gibson, the Dodgers might be desperate. His 4th pitch was a ball outside, going a little farther to see if Kirk would bite beyond the fringe. He didn’t. Since “Eck” didn’t throw over before the 4th pitch, Davis attempted a steal on the 5th. Gibson had his best swing yet, but fouled it back. Eckersley didn’t think Davis would steal on consecutive pitches, and he was correct, but threw “Ball 2” in the process. Before his 7th pitch, he threw to first base again. But on the pitch to Gibson, the ball was further outside, and Davis successfully stole second base, much to the consternation of LaRussa, Eckersley, and the “As” dugout as the count rose to 3 and 2.

The situation had not developed the way Eckersley intended. Gibson’s impotent yet “frisky” at-bat posed a conundrum whose immediate solution never materialized. So there was only one direction in which to go! As Dennis Eckersley was truly an adroit “student of the game”, he, like the many who had come before him, usually observed Masterful Warren Spawn’s advice when administering to their trade: “It is the batter’s duty to have good timing and rhythm to perform effectively, while it is the pitcher’s duty to off-set that rhythm and timing with variable speeds and placement of pitches.”

As for Gibson the batter, he had neither rhythm nor timing when he came to the plate. But through the course of his gauntlet-like “trial-by-pitch” he had developed both to a rather insignificant level. Now, it was thought by “Eck”, to end this dilemma. He knew what he had to do. He’d done it before, with great success. And he will do it, NOW! The Game wasn’t necessarily on the line, if his strategy failed. Gibson would walk, and the Dodgers would still have a runner in scoring position, presenting merely a secondary condition that would quickly be dismissed. But “Eck” was confident, he could not fail. “This is absolutely the ‘last hand’.”

All the “Cards” being dealt, Eckersley landed (in Poker parlance) a 4th Ace, while Kirk had a pair of Jacks and the 7, 8, 9 of Clubs. Kirk could have kept the pair and thrown the other 3 away, but instead threw the Jack of Hearts. The statistical probability for Eckersley’s success was astronomical! Kirk Gibson seemed to have been abandoned by the “gods” and his mythological legend was about to become irreparable. The most he could hope for was simply a mimesis of that “Luis Gonzalez” swing, and flare a base hit that might tie the game. But in Eckersley’s mind, a game-ending out is all Gibson’s “gunna” get!

There’s the tying run on second base. Eckersley is in his “stretch”. The count is 3 and 2. “Eck” is about to deliver the most potent pitch in his repertoire. The Dodger dugout is ecstatic. Now, with the fleet-footed Davis in scoring position, a base-hit would tie the game, and that is all and the best they could expect from their forlorn hero. But Eckersley had other plans! And, what was Gibson himself thinking?

Just before Eckersley was to deliver his “secret” pitch, Kirk abruptly stepped out of the batter’s box, as if to regain his composure in this momentous circumstance. But, in that instant, a higher source seemed to beckon him to recall an otherwise innocuous fact that Kirk had read on a report prepared by an astute and meticulous “scout” before the playoffs began. After pondering the present situation, all statistical possibilities seemed to be aligned in a favorable position. And the curtain was about to fall with a dramatic conclusion, on one of these conquering heroes, each with his own weapon of invincibility in hand (Reminiscent of the final poker-hand in the movie, “The Cincinnati Kid”). But which will project the image of “The Man”?

Kirk looked toward the mound, then stepped into the “Box”, knowing he had all the information he needed (his final card was dealt). But is his faith in his belief strong enough; and will his mind’s commitment to act unflinchingly, in spite of his apparent bodily condition, enable his warrior-heart? 55,000 spectators are about to find out as well.

Neither antagonist is smiling but each exudes an indefinable confidence, even while knowing well that “one will die today”. Eckersley takes his stretch and prepares his “Load” for delivery. Gibson makes a final but ominous mental query designating his unquestioning tact as “the die is cast” once more, “Sure as I’m standing here, partner, you’re going to throw me that “back-door” slider, aren’t you?”

As the pitch leaves his hand, Eckersley recognizes the ball’s trajectory to be perfect, right where he wanted it. With all the pitches he had thrown, he knew Gibson would see the ball moving directly toward the outside. He also thought Gibson’s quick sense would assume that since his side-armed fast ball “tails”, the pitch’s destination would obviously move farther outside for a ball. He was expecting Kirk to momentarily relax, and not have enough time to respond to the pitch’s abrupt deviation of speed and direction, until it was too late – The “Aces” were “face-up”!

“Sure enough”, realized Kirk, upon first glance! His “absolute faith”, and patience allow him to wait. He’s not yet lifted his front foot as he did previously while expecting Eckersley’s fast ball. An extra nanosecond of Time is in his favor. “Now, all I have to do is get my timing right, to be able to explode at the precise moment!” In his extremely “closed-stance”, as he discerned the ball’s outside trajectory, he waited until he could detect its subtle and abrupt turn toward him. Then his front foot exaggerated its deliberate stride toward third base, as his body was “gathering” its forces to uncoil as his foot would plant into the ground.

Eckersley couldn’t help but notice that Gibson’s physical demeanor was uncommonly composed as he unobtrusively glided in the direction from which the ball was finally descending (as if he knew what was coming). “Eck” saw Kirk’s foot plant, his body uncoil, his arms extend, and in a final explosive lunge of shoulders, hands and wrists observed the bat contact the ball with an uncanny perfect synergy that launched the round projectile with improbable force in the opposite direction from which it came.

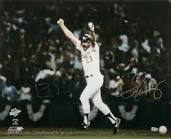

With all spectators and both dugouts watching in apparent disbelief, the ball kept rising and carrying farther and farther in its ellipticity until it finally disappeared over the right-field wall, as Kirk’s final card resoundingly struck the table as a 10 of Clubs – and a “Straight Flush”. Throughout the day not a hint of joy was expressive of the face of Kirk Gibson, only a stoic facade hiding pain, disappointment, resentment, and disdain for his helpless and impotent condition. As the follow-through of his celestial swing of bat was complete, and he cautiously embarked on an unrehearsed, and as yet undefined, trek, an observer could detect a gradual change in facial disposition. The remorseful look of indifference was suddenly transforming into a heavily distinguishable canvas of ecstatic jubilation. And in a moment of triumphant glory he pumped his bent right arm in successive punches along the side of his beleaguered body after the subjugated leather-bound projectile did indeed traverse the height of the outfield fence for an uncontested, historic “masterstroke” (Tour De Force) of amazing ramifications, the conclusion of which would be directly revealed.

The instant of evidentiary proof of Gibson’s success immediately transformed the hopeful yet solemnly-cautious dispositions of Dodger fans and Teammates (who hadn’t really believed in “Santa Clause”) into genuinely faith-filled followers who, at that “holy instant,” probably could have moved a mountain or two. The dug-out Dodgers were streaming out onto the field, arms flaying and voices shouting “Hallelujah” (from the roof-tops) to their “resurrected “messiah” as he buoyantly circumnavigated the bases in all but reconstructed, glorified form.

His amazing feat did provide a Home Run of incomparable distinction. And it did win that First Game of the “Series”, in abrupt and miraculous fashion. But the intangible essence of that single act of unfathomable “Heroism” also unlocked a momentarily imprisoned spirit of Team unity that suddenly “empowered” the Dodgers to claim the 1988 World Series Title, even without Kirk playing another moment of any of the remaining 4 games. Kirk Gibson’s Home Run was truly the “single-most amazing performance piece in Sports history.”

Postscript:

As unlikely as Kirk Gibson’s conquest was, at that momentous October event, what more climactic expression of exaltation could be spontaneously delivered than that spoken by Baseball’s “immortal bard”, Vin Scully, when he exclaimed, as Kirk was rounding the bases, “In a year that has been so ‘improbable’, the ‘Impossible’ has occurred.” Truer words were never spoken. No one in the world could have expected Gibson’s humble yet triumphal salute, “I came; I saw; I conquered!” And for the last 25 years, legions of followers have echoed the words of another prominent and renowned sportscaster (Joe Buck) as he commented repeatedly, in breathless exuberance, “I DON’T BELIEVE WHAT I JUST SAW! I DON’T BELIEVE… WHAT I JUST SAW”! Nothing in Sports History can equate to Kirk Gibson’s “improbable” and “impossible” act of courage and accomplishment. The only historical event that would have shared in equipollence would have been “The Battle of Thermopylae”, if the Spartan warriors had defeated the Persians.