The three major components in effecting the proper technique for fielding a baseball on the infield are these: balance, vision, and power. As play is initiated, fielding readiness implies being in a low balanced position , eyes focused on the point where the ball would contact the bat, and the body responding to that instant with preliminary movement to brace himself in anticipation of the ball being hit to “him.” If it becomes evident that the play is “his,” the preliminary action sets the stage for a quick sequence of smooth, rhythmical, ballet-like movements that follow

, eyes focused on the point where the ball would contact the bat, and the body responding to that instant with preliminary movement to brace himself in anticipation of the ball being hit to “him.” If it becomes evident that the play is “his,” the preliminary action sets the stage for a quick sequence of smooth, rhythmical, ballet-like movements that follow , in preparation for engaging the on-coming ball, as well as completing the play to its entirety.

, in preparation for engaging the on-coming ball, as well as completing the play to its entirety.

An infielder establishes stability and balance to perform his task when his center of gravity is low. His ability to see the ball most clearly is determined by the extent to which his eyes are on a parallel level to the ball, and the degree to which the body and head maintain a stable vehicle for proper focus. Power is generated most effectively with the body in a stable, balanced position, from which all movements can be produced most speedily, and with a minimum strain to accompanying body parts.

If the outfield can be a lonely place to play, the infield is just the opposite in that there is a more heightened sense of camaraderie  as well as imminent expectation. Players are in close proximity to each other. They talk to one another. They communicate more easily. They don’t seem to have a great need to be highly creative; they usually have more action than they want or can handle. Rather than having to be “fast” runners, their effectiveness is determined by how “quick” they are in a confined area. They don’t cover vast territory, but must be extremely adept at moving laterally

as well as imminent expectation. Players are in close proximity to each other. They talk to one another. They communicate more easily. They don’t seem to have a great need to be highly creative; they usually have more action than they want or can handle. Rather than having to be “fast” runners, their effectiveness is determined by how “quick” they are in a confined area. They don’t cover vast territory, but must be extremely adept at moving laterally  with quick bursts to handle “bullet-like” projectiles with the courage, confidence, and agility of a “mongoose.”

with quick bursts to handle “bullet-like” projectiles with the courage, confidence, and agility of a “mongoose.”

“Ballerina-like” footwork and the hand and finger dexterity of a heart surgeon typify the common physical characteristics of a professional infielder . There is one quality that no infielder can be without—Courage! All infielders have it. It’s never a case of one having more than another. It is only a question of whether or not he’ll “muster it up” consistently, on every ball hit, as evidenced in the occasional “Ole.”

. There is one quality that no infielder can be without—Courage! All infielders have it. It’s never a case of one having more than another. It is only a question of whether or not he’ll “muster it up” consistently, on every ball hit, as evidenced in the occasional “Ole.”

The best infielders use every conceivable means to gain an advantage over the ferocious ground-ball that would like to “eat them up.” Fielding ground balls properly involves a physical procedure which runs contrary to every human instinct to self-preservation—to lean forward as low as possible to the turf while a hard hit grounder is approaching your position. It’s like going nose to nose with a rattlesnake. Now, the procedure is sound because it allows the fielder a sure tracking view from ground level.

Fielding ground balls properly involves a physical procedure which runs contrary to every human instinct to self-preservation—to lean forward as low as possible to the turf while a hard hit grounder is approaching your position. It’s like going nose to nose with a rattlesnake. Now, the procedure is sound because it allows the fielder a sure tracking view from ground level.

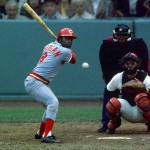

A tennis player returning a serve , and a batter attacking a pitched ball

, and a batter attacking a pitched ball , understand the value of seeing the in-coming object on a parallel level. But an infielder has the added dimension of coping with the traumatic possibility that the ball could easily pop up and “bite off his nose,” loosen some teeth, or cause irreparable damage to his prospects for video endorsements.

, understand the value of seeing the in-coming object on a parallel level. But an infielder has the added dimension of coping with the traumatic possibility that the ball could easily pop up and “bite off his nose,” loosen some teeth, or cause irreparable damage to his prospects for video endorsements.

Third and First basemen hold down positions referred to as the “hot corners.” Playing “even” with their respective bases, these two infielders are closer to the batter than any one besides the pitcher and catcher. But only the pitcher is subject to more hazardous ballistic encounters with a baseball than the third and first basemen. Since there are more right-handed batters in all of Baseball, then presumably a third baseman would be in possession of the hotter of the “hot” corners

these two infielders are closer to the batter than any one besides the pitcher and catcher. But only the pitcher is subject to more hazardous ballistic encounters with a baseball than the third and first basemen. Since there are more right-handed batters in all of Baseball, then presumably a third baseman would be in possession of the hotter of the “hot” corners . But in general, the sense of “imminent responsibility” is the same, especially when the first baseman “holds” the runner.

. But in general, the sense of “imminent responsibility” is the same, especially when the first baseman “holds” the runner.

While the choreography involved in fielding ground-balls amongst infielders is generally the same, there are subtle differences in “prep-time” (stance, as pitch is being delivered) between the “hot-corners” and “middle-infielders.” Time and speed are always of the essence. For obvious reasons, to be able to respond quickly at the “corners,” those fielders assume a “tunnel-vision” mentality, positioning their bodies with a low center of gravity with eyes focused at the point where the bat is likely to strike the ball to force it in their directions. The low positioning of the body is for heightened anticipation that the ball will be hit on the ground where the eyes are able to make more acute visual contact

with eyes focused at the point where the bat is likely to strike the ball to force it in their directions. The low positioning of the body is for heightened anticipation that the ball will be hit on the ground where the eyes are able to make more acute visual contact . Anything other than a solidly hit “grounder” is a welcomed sight to any infielder. The adjustment to “lined-drives” and “pop-ups” is minimal, hence nothingmuch to fear. However, much applause is heralded by all onlookers after a leaping or lunging third or first “sacker” spears a wicked “lined-shot.”

. Anything other than a solidly hit “grounder” is a welcomed sight to any infielder. The adjustment to “lined-drives” and “pop-ups” is minimal, hence nothingmuch to fear. However, much applause is heralded by all onlookers after a leaping or lunging third or first “sacker” spears a wicked “lined-shot.”

The shortstop and second baseman can assume a more relaxed posture  as the pitch is being delivered because they are farther away from the batter and have a panoramic view of the entire infield, which facilitates a surer sense of how the ball will come off the bat. If the ball is hit to either player, he quickly assumes the characteristic fielding position, body lowered and “face to the ball,”

as the pitch is being delivered because they are farther away from the batter and have a panoramic view of the entire infield, which facilitates a surer sense of how the ball will come off the bat. If the ball is hit to either player, he quickly assumes the characteristic fielding position, body lowered and “face to the ball,” then glides through the ball while preparing to engage the “throwing mechanics.”

then glides through the ball while preparing to engage the “throwing mechanics.”

The rhythm which all infielders develop when learning to “attack” the infamous batted-ball is a defensive-mechanism established to preoccupy thought from petrifying with fear the mind of the inanimate body. It’s like reverse psychology! The more fearful you are, the more you must look to be fearless. Animated body parts unconsciously convey this message . No one is totally fearless, but a sense of confidence does much to deny fear its manifestation—hesitation, misjudgment, over-anxiousness, mental and physical error.

. No one is totally fearless, but a sense of confidence does much to deny fear its manifestation—hesitation, misjudgment, over-anxiousness, mental and physical error.

Confidence is enhanced as one becomes assured of his ability to counteract the undermining element that elicits fear. Quick reflexes of head, neck, and hands are the usual defenders against the perpetrator of fear on the infield—that little bolt of “white lightning.”

Being hit in any part of the body by a thrown or batted baseball is not an experience that most individuals anticipate with relish. In fact, there are many instances where prospective players of the “game,” from “little-league” to “college-ball,” decided to “hang-em-up” after being hit too many times (or even once). An outstanding 250 pound line-backer on a prominent college football team, who never hesitated taking on 300 pound line-men or powerful running-backs (or even a “Mack-Truck”) stopped playing baseball in high-school because he couldn’t get over the thought of being hit by that little white, 5 ounce, leather-bound projectile.No sane person would intentionally subject himself to the continuous prospect of physical abuse unless there was a sense of tangible hope for lessening the chances of undesirable engagement. The only legitimate solution to “the dilemma” is a “skill-development” progression that affords an “inoculatory-effect” by decreasing physical intensity and promoting a build-up of resistance to the initial, overwhelming, mental effect that the image of the “Hard-Ball” projects.

Little-leagues” have increased enrollment recently by prudently affecting the density of the ball used at their lowest levels of play, to protect their youngest prospects from experiencing the debilitating trauma of hard-ball contusions that could curtail their desires to continue to learn the game. This “inoculation period” enables the players to develop the initial skills with less trepidation, and hopefully become proficient enough to counteract the effects of higher intensity in the future. Since “Fear” is what ultimately impedes progress of every sort, any tool that would lessen its effects could only be thought of as positive and promoting a better, more healthful learning environment for any of life’s endeavors (fielding ground-balls and batting included).

Ultimately, if you’re going to play Baseball you have to either overcome or cope with the fear of “ball-contact.” The “Seasoned—Veteran” has learned to “shrug it off” as merely part of the game that his sharply defined reflexes can help him cope with most of the time. The “Metaphysically-astute Veteran” seems to be able to overcome the physical trauma by denying that it has any affect on him by showing his disdain with stoic indifference.

The “Seasoned—Veteran” has learned to “shrug it off” as merely part of the game that his sharply defined reflexes can help him cope with most of the time. The “Metaphysically-astute Veteran” seems to be able to overcome the physical trauma by denying that it has any affect on him by showing his disdain with stoic indifference.

At this point of considering the means to establishing optimal fielding prowess it may become evident that playing the game of Baseball at the highest level may not be for everyone. But the opportunity to get to that point and realize what it really takes to become a “big-leaguer” is a valuable lesson for which to hold enormous pride and appreciation for having gone through one of life’s human gauntlets that will no doubt serve one well in any future challenging encounters.

Coming Soon: A New Series entitled – Assisting those who would and should be Great, to BE GREAT! First three candidates will be Giancarlo Stanton, Yu Darvish, and Aaron Judge.