“A new name for an ailment affects people like a Parisian name for a novel garment. Every one hastens to get it.” These words were written in the late 19th century by Mary Baker Eddy, a highly astute meta-physician who keenly observed the prevalent trend of the medical profession, along with the unwitting press, to exacerbate legitimate attempts to “heal” by “…giving names to dis-ease and printing long descriptions which mirror images of disease distinctly in thought.” “…A minutely described disease costs many a man his earthly days of comfort.” “Many a hopeless case of disease is induced by a single post mortem examination, – not from infection nor from contact with material virus, but from the fear of the disease and from the image brought before the mind; it is a mental state, which is afterwards outlined on the body. We should master fear, instead of cultivating it. It was the ignorance of our forefathers, in the departments of knowledge now broadcast in the earth, that made them hardier than our trained physiologists…”

In the “beginning” an older pitcher (the real Tommy John) whose 12 year career was quietly dissolving into mediocrity due to recurring elbow injuries decided to take on the role of “guinea-pig” in an experimental surgery by not-yet-eminent Orthopedic physician-surgeon, Dr. Frank Jobe. After his surgery, Tommy John pitched even more successfully for another 14 years. The “Ulnar-Collateral-Ligament” operation was henceforth named “Tommy John” surgery, after its Prototype. Since that initial 1974 operation, thousands of similar procedures have been performed on professional athletes (mostly baseball pitchers) as well as amateurs, and many a baseball career has lengthened. So, that is GOOD, from a therapeutic standpoint! But what can be done as a Primary preventive measure, since even “Tommy-John” is not 100% successful?

In the “beginning” an older pitcher (the real Tommy John) whose 12 year career was quietly dissolving into mediocrity due to recurring elbow injuries decided to take on the role of “guinea-pig” in an experimental surgery by not-yet-eminent Orthopedic physician-surgeon, Dr. Frank Jobe. After his surgery, Tommy John pitched even more successfully for another 14 years. The “Ulnar-Collateral-Ligament” operation was henceforth named “Tommy John” surgery, after its Prototype. Since that initial 1974 operation, thousands of similar procedures have been performed on professional athletes (mostly baseball pitchers) as well as amateurs, and many a baseball career has lengthened. So, that is GOOD, from a therapeutic standpoint! But what can be done as a Primary preventive measure, since even “Tommy-John” is not 100% successful?

If you were privy to the “Round-Table” discussion sponsored by the MLB network, and hosted by Bob Costas, along with Jim Kaat, Tom Verducci, Drs. Andrews and Alchek, and Tom House, your attention was brought to a number of physiological points of perspective that clearly established the many facets of the dilemma now facing the Baseball Community, from the Major Leagues down through Sand-lots. Why has this dis-ease now become so prevalent amongst our young and most promising pitching prospects? And, can anything be done to eliminate or at least diminish accounts of this trend from continuing at such an awkward and “terrifying” pace?

The first line of defense against this seemingly insidious attack on the integrity of the Game of Baseball itself, as well as the integrity of the individual(s) directly afflicted by, or potentially vulnerable to, the otherwise debilitating nature of this career-ending physical impairment is to be “not afraid.”

The first line of defense against this seemingly insidious attack on the integrity of the Game of Baseball itself, as well as the integrity of the individual(s) directly afflicted by, or potentially vulnerable to, the otherwise debilitating nature of this career-ending physical impairment is to be “not afraid.”

When intelligent, well-intending, spokes-people imply that the game must somehow be restricted in various ways in order to protect “enthusiastic-youth” from their ignorance of predatory aspects of their “favorite game,” “FEAR” is at least temporarily holding preponderance over the better judgment to be afforded. Lowering the mound, or pitching on “flat-ground,” playing other sports, taking a few months off, all or any for the purpose diminishing the prospect of shoulder and elbow injury seems analogous to “burning down the barn to get rid of rats”! There is however reason to applaud the idea that anyone (youngster or adult) attempting to become a “Pitcher” should focus on the proper technique for throwing a ball accurately with as much velocity as the natural, smooth, mechanical motion of the entire body-arm continuum would allow. (Any attempt to accelerate body growth and development with premature muscular enhancement only endangers the physical infra-structure of ligaments and tendons, as seen in careless and illegal steroid use.)

The following exegesis comes from Chapter Two of my Book, The Principle of Baseball – And All There is to Know about Hitting.

Throwing a Baseball

Nothing happens in a baseball game until after the first pitch is thrown. Throwing a baseball then seems to be a very important part of the game. In fact, Pitchers (and Power-Hitters) are considered to be the most prominent characters in the game. The ability to throw the ball hard and far evokes a mythical aggrandizement from which legends are made. What is it that enables one individual to throw harder and farther than another? Are some people blessed with natural ability to throw better than others? It’s hard to say when and how an individual developed certain physical characteristics associated with strength, or whether he acquired some unusual pre-natal condition that facilitated an accentuated leverage point to produce a greater aptitude for throwing! But two things are certain: it has been observed countless times, that the seemingly “gifted” athlete cannot reach his/her full potential unless the proper body-mechanics are employed; and the “not-so-gifted” sometimes attains a higher level of success with intellectual astuteness and the utilization of proper body-mechanics. It is common to evaluate a player’s throwing ability by saying, “. . . he/she has a strong or weak arm.” It is incorrect, though, to assume that the power of the throw is determined by the strength of the arm. The main power source for throwing is the “Body.” The arm provides only a fraction of the power. From the coordinated precision of the movement from the feet to legs, to hips, to torso, to shoulders, to arm(s), elbow, wrist, hand, and fingers is the ultimate power registered in the “perfect throw.”

Obviously, the player with the stronger body and arm, who applies the mechanics perfectly, will be more effective than the weaker player. Also, not generally observed is the fact that, in throwing a baseball effectively, a principle law of physics always comes into play, namely, “. . . every action has an opposite and equal reaction.” If a player is right-handed, to be totally effective, he must use the left side of his body with the same intensity as he does the right, while performing the throw. This will enhance the power, as well as help secure balance with the proper follow-through. This application is analogous to that which a Karate Master invokes to maximize the power of a “strike” or “punch.” The force exerted backward(in “turnstile” fashion), by the front side of the body, not only accentuates the forward movement of the backside, but magnifies it, adding considerable power to the throw. (The same principle is expressed in swinging the bat.) The stronger the body the greater the possibility for a strong throw, as long as the application of the proper mechanics for movement of shoulder(s) and arm come into play. Unfortunately, the stronger the body, the greater is the opportunity for injury to the shoulder and arm if the application of proper mechanics is not enforced.

Obviously, the player with the stronger body and arm, who applies the mechanics perfectly, will be more effective than the weaker player. Also, not generally observed is the fact that, in throwing a baseball effectively, a principle law of physics always comes into play, namely, “. . . every action has an opposite and equal reaction.” If a player is right-handed, to be totally effective, he must use the left side of his body with the same intensity as he does the right, while performing the throw. This will enhance the power, as well as help secure balance with the proper follow-through. This application is analogous to that which a Karate Master invokes to maximize the power of a “strike” or “punch.” The force exerted backward(in “turnstile” fashion), by the front side of the body, not only accentuates the forward movement of the backside, but magnifies it, adding considerable power to the throw. (The same principle is expressed in swinging the bat.) The stronger the body the greater the possibility for a strong throw, as long as the application of the proper mechanics for movement of shoulder(s) and arm come into play. Unfortunately, the stronger the body, the greater is the opportunity for injury to the shoulder and arm if the application of proper mechanics is not enforced.  If the power generated by the body is complete, the torque action of the twisting hips and torso could be too great for a shoulder and arm ill prepared to deliver the final dimension of the throw. If the shoulder is not locked into a position of stability, to launch the (bent) arm and that (5-ounce) ball forward at the precise time, the strain of having transported the spherical object from the point of origin to destination could have a deleterious effect on the accompanying extremities. The weight of a 5-ounce object doesn’t seem like it should have any major affect on the throwing apparatus of a strong, well-conditioned athlete. But if you think about the strain one feels in his shoulders, while merely extending the arms outwardly, away from the body, and sustaining that position for a period of time, you could see how any additional weight would accentuate the strain. Even more stress would be added, if you realize the extra force exerted on “those joints,” by the weight of the moving arm and ball.

If the power generated by the body is complete, the torque action of the twisting hips and torso could be too great for a shoulder and arm ill prepared to deliver the final dimension of the throw. If the shoulder is not locked into a position of stability, to launch the (bent) arm and that (5-ounce) ball forward at the precise time, the strain of having transported the spherical object from the point of origin to destination could have a deleterious effect on the accompanying extremities. The weight of a 5-ounce object doesn’t seem like it should have any major affect on the throwing apparatus of a strong, well-conditioned athlete. But if you think about the strain one feels in his shoulders, while merely extending the arms outwardly, away from the body, and sustaining that position for a period of time, you could see how any additional weight would accentuate the strain. Even more stress would be added, if you realize the extra force exerted on “those joints,” by the weight of the moving arm and ball.

“The farther away the ball moves from the body, as the arm is preparing to throw it, the heavier the weight will be to the strain of the shoulder (and elbow).” As the ball is being prepared for its launch from the thrower’s hand it should remain as close as possible to the “Body-Proper,” while the arm is “whipping” itself to the forward thrusting position. (Nolan Ryan and M. Tanaka are the best exponents of this “principle.”)

“The farther away the ball moves from the body, as the arm is preparing to throw it, the heavier the weight will be to the strain of the shoulder (and elbow).” As the ball is being prepared for its launch from the thrower’s hand it should remain as close as possible to the “Body-Proper,” while the arm is “whipping” itself to the forward thrusting position. (Nolan Ryan and M. Tanaka are the best exponents of this “principle.”)

It has been accurately stated that the best of throwers has an arm delivery of the ball that resembles the action of a fast moving whip. To acquire the “correct” type of “whip-action” arm movement, the thrower must proceed with the following arm sequence, after the ball is taken out of the glove (presuming the arm is in a bent position as the hand and ball come out of the glove). The back and middle of the shoulder (posterior and lateral parts of deltoid muscle, specifically)

It has been accurately stated that the best of throwers has an arm delivery of the ball that resembles the action of a fast moving whip. To acquire the “correct” type of “whip-action” arm movement, the thrower must proceed with the following arm sequence, after the ball is taken out of the glove (presuming the arm is in a bent position as the hand and ball come out of the glove). The back and middle of the shoulder (posterior and lateral parts of deltoid muscle, specifically)  brings the hand and ball from the glove, prominently displaying the bent elbow, with the hand and ball apparently hanging below momentarily, just above the back hip.

brings the hand and ball from the glove, prominently displaying the bent elbow, with the hand and ball apparently hanging below momentarily, just above the back hip.

(Incidentally, the thrower’s position at this point looks similar to that of a person holding a bucket of water by the handle, and has just lifted it upward along the side of his body.) As the thrower moves sideways toward the “target,” a low center of gravity presents his body as in a low sitting position. As the front foot plants (toes pointed to-ward the target), the hips and torso begin to turn with the help of the bent front leg that is in the process of straightening.

(Incidentally, the thrower’s position at this point looks similar to that of a person holding a bucket of water by the handle, and has just lifted it upward along the side of his body.) As the thrower moves sideways toward the “target,” a low center of gravity presents his body as in a low sitting position. As the front foot plants (toes pointed to-ward the target), the hips and torso begin to turn with the help of the bent front leg that is in the process of straightening.

The backside (hip and torso) gains momentum from the back leg, with its pulling bent knee and pivoting foot. The throwing shoulder quickly rotates outwardly, to force its bent arm to bring the hand and ball upward, slightly above the shoulder. At this point, the muscles of the outwardly-rotated shoulder contract quickly (without hesitation), along with those of the entire upper body.

The backside (hip and torso) gains momentum from the back leg, with its pulling bent knee and pivoting foot. The throwing shoulder quickly rotates outwardly, to force its bent arm to bring the hand and ball upward, slightly above the shoulder. At this point, the muscles of the outwardly-rotated shoulder contract quickly (without hesitation), along with those of the entire upper body. As the shoulder thrust is completing its full range of rolling-forward-motion(anterior deltoid), the arm quickly extends

As the shoulder thrust is completing its full range of rolling-forward-motion(anterior deltoid), the arm quickly extends

forwardly as forearm is in full pronation (not sideways

forwardly as forearm is in full pronation (not sideways ), as the wrist snaps the fingers through the center of the ball (fingers straight, perpendicular to the ground) at the point of release. The coordinated action of the entire body (right and left sides) provides the power for the correct arm movements to occur rapidly (and safely), and thus sustain a whip-like action(where elbow never snaps closed –

), as the wrist snaps the fingers through the center of the ball (fingers straight, perpendicular to the ground) at the point of release. The coordinated action of the entire body (right and left sides) provides the power for the correct arm movements to occur rapidly (and safely), and thus sustain a whip-like action(where elbow never snaps closed –  ) to move through the “throw” like a wave of tremendous force. END

) to move through the “throw” like a wave of tremendous force. END

It is not to say that anyone following the correct throwing procedure, as described above, will be assured of never having to incur “Tommy – John” surgery, for there are many factors involved, any of which could subject a player to vulnerability. Lack of muscle-conditioning, over-conditioning, inappropriate training techniques, misunderstanding of how to enhance power, strength, endurance, and application of skills of “specificity” regarding the game of baseball all come into play when evaluating the safest way to procure a long and illustrious career, as a pitcher or any fielding position. You can’t have “flabby” muscles and expect them to be able to contract quickly and with power to facilitate movement for optimal proficiency on the professional baseball field. But excessive weight-training for baseball seems equally inappropriate to facilitate the actions needed on a baseball field. Why would a pitcher need to “Bench-press” in excess of 100 lbs., or “curl” more than 10 or 15 lbs when the ball he is expected to have mastery over weighs but 5 ounces? (The standard for extreme “Pitcher-Workouts” used to be Nolan Ryan, and I never saw a video of him working with more than 6-8 lb. “dumbbells”.)

When Kevin Brown

took the San Diego Padres to the World Series, he was a well-conditioned athlete-pitcher whose arm and body were so fluid that he exuded a particularly anatomical freedom as his live, moving fast-ball flowed almost effortlessly from his flawless delivery. After “Free-agency,” the next time I saw him he had a chiseled look of statuesque proportions with which he never again threw with his former magnificence.

took the San Diego Padres to the World Series, he was a well-conditioned athlete-pitcher whose arm and body were so fluid that he exuded a particularly anatomical freedom as his live, moving fast-ball flowed almost effortlessly from his flawless delivery. After “Free-agency,” the next time I saw him he had a chiseled look of statuesque proportions with which he never again threw with his former magnificence.

When Mohammed Ali worked out, he simply simulated the movements of his Trade, but with the intention of developing his muscles to move more quickly and powerfully with repetitious actions that naturally increased muscular strength to increase speed and stamina.

All Satchel Paige did to stay in shape and to maintain his physical condition to perfect his “Craft” was “Throw,”

and didn’t let any wrong thinking affect his “positive attitude” about himself and his functionality.

and didn’t let any wrong thinking affect his “positive attitude” about himself and his functionality.

Ru

Ru

“Funny what a few No-hitters do for a Body.”

“Funny what a few No-hitters do for a Body.”

The best conditioning methods for any baseball player is simply to simulate the movements that he would perform during the course of a game. But after the initial “warm-up” period, simulate those movements rigorously, at full speed, and perfectly, with thoughtful intention. Jogging laps does not promote proficiency for your “craft” – practice sprinting (even pitchers – for explosive intent). Players who pull hamstring muscles do so because their muscles have lost their sense of former proficiency. They forgot how to contract for the given task, then strain to accommodate the immediate need.

Advocates and critics of the training “tool” known as “Long-Toss” have reason to speculate on the propriety of the activity. If the intent of the “thrower” (pitcher or “…fielder”) is merely to test or enhance the strength of his “arm” by lofting the ball 400 feet,  then critics are justified because there is no purposeful intent in such action, especially if it is repeated continuously. IF a pitcher (and even an Out-fielder) repeats such body and arm action countless times before a game (or even days before he is actually pitching) how does he expect to re-train his body and arm to function optimally when “it counts” under crucial game conditions.

then critics are justified because there is no purposeful intent in such action, especially if it is repeated continuously. IF a pitcher (and even an Out-fielder) repeats such body and arm action countless times before a game (or even days before he is actually pitching) how does he expect to re-train his body and arm to function optimally when “it counts” under crucial game conditions.

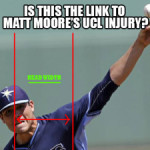

A pitcher can exceed his normal 55 to 60 feet throwing distance when “training” as long as his “release-point” and body-alignment are at least close to that with which he delivers the ball to the plate. A good technique when either the pitcher or fielder “needs” a longer distance to accommodate his “psyche” is to accept the “one-bounce” principle instead of throwing the complete distance in the air. Repeated throwing with a high arc produces a body and arm action that induces a last second power-thrust of the elbow joint because the shoulder usually has reached its maximum range of motion – thus possibly presenting a vulnerability factor to the “Ulnar-Collateral-Ligament,” whose stability of the elbow is always jeopardized when “Pronation” and extension of the arm occur in such abrupt fashion. When pronation occurs after the arm has extended, then the elbow falls into “double-jeopardy” because the fore-arm and wrist are acting more independently than if the shoulder and triceps were actively assisting the power-flow. Tennis players are particularly vulnerable because the striking point is high in order to accommodate an acute descending plane of the ball.

(Incidentally, Roger Federer’s follow-through is unquestionable.)

(Incidentally, Roger Federer’s follow-through is unquestionable.)

Can anyone notice the peculiar habits that are a common characteristic of those who are most susceptible to incur shoulder or “Tommy-John” surgery?

The “Specificity of Motion-Movement” Principle is probably the best policy to practice if any pitcher or fielder would want to train his body and arm properly and condition them to sustain the physical and mental well-being during a Baseball career.

Coming Soon: The D.H. is the Only Way to Go!